I read the e-mail twice. A longstanding client was asking whether they could show on their website a video they found on YouTube. They explained that they thought that could use the video since it was their understanding that things online, like YouTube, are public domain unless they specifically state that you need permission to use them. I quickly typed back a response advising that it is best to proceed on the assumption that everything available online is protected in some fashion and can only be used with permission.

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard something along these lines—the internet has long been analogized to the Wild West when it comes to intellectual property—and I knew it wouldn’t be the last. It is another persistent myth with no basis in the law. While it may be possible to copy online content for your own use without anyone knowing, understanding why online content should not be considered free for use can help avoid cease and desist letters from content owners and, potentially, adverse judgments.

Images/Songs/Videos

There is a lot of content that is available online: text, images, songs, videos, you name it, it is available. But the mere fact that content is available does not mean it is free for you to use.

U.S. copyright law provides that copyright protection is available for creative works such as images, videos or songs as soon as they are created. Any U.S. based creator who wants to protect their work should register their work with the U.S. Copyright Office; having a registration certificate is a pre-condition to filing a lawsuit for copyright infringement. To be clear, though, the fact that a creator may not have a copyright registration does not mean that a work is free to use. Copyright registrations can be obtained on an expedited basis (usually within a week) by anyone willing to pay the Copyright Office’s fee.

If the work is a creator’s “signature” (if a creator includes a blue dog in each of their paintings, for example, or if a creator uses the color red on the underside of each shoe that they make), then the creator might also be able to assert a claim for unfair competition. The basis for such a claim would be that the appropriator’s use is likely to cause consumers to be confused about the source of the appropriator’s work—consumers would think that the work is either by the creator, or sponsored or endorsed by the creator, when in fact it is not.

Thinking that a creator won’t learn of your use is not a safe way to proceed, either. Most professional photographers license their images to agencies, which then license those photographs to others for use. Those agencies also search for unauthorized uses. When they find them, they generally send letters advising that the use is unauthorized and asking for a royalty payment for the past use. Such agencies use bots and other tools to search the internet and identify unlicensed uses and are not likely to just give up if they are ignored. On top of that, there are websites, such as Pixsy, which will track photos and act when unauthorized uses are found.

Posting something to YouTube, Twitter or Instagram generally does not deprive the creator of their rights. For example, YouTube’s terms of service say that a creator retains their rights in work they upload to YouTube, and that they grant YouTube and users of YouTube the right to watch any content they have uploaded, but not the right to use it on their own website.

Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC—Do Embedded Tweets Infringe?

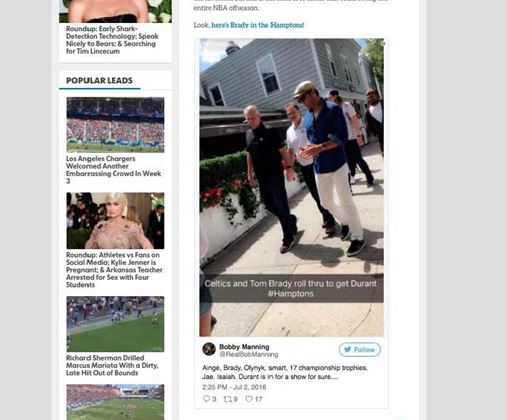

The internet makes it easy for people to share things. Sometimes, though, the mere sharing of an image can give rise to liability for infringement, as exemplified by a recent case involving a photograph of New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady and several major news blogs and outlets.

In July 2016, Justin Goldman, a photographer, took a photograph of Tom Brady and others on the street in East Hampton. He subsequently uploaded the photo to his Snapchat Story, and the photo went viral. It was eventually uploaded (Tweeted) to Twitter by several individuals. The news outlets published articles featuring the photograph, embedding the Tweet into the articles they wrote. One example is shown below.

The embedded Tweets incorporated code that directed web browsers viewing the article to retrieve the photo from third party websites (in this case Twitter’s servers); the blogs and news outlets did not host the photo on their own servers. As a result, the photo was seamlessly integrated into the article presented to readers, who had no idea where the photo was hosted.

Goldman, who owns the copyright in the photo, sued the blogs and news outlets for copyright infringement. Goldman asserted that even though the photo was hosted on Twitter’s servers, the display of the photo on the blogs and news outlet websites infringed his right to display the photo. The court, noting the broad language in the Copyright Act intended to make the Act applicable to new technologies, agreed. In doing so, the court declined to adopt a line of cases holding that infringement depended, in part, on where an image is hosted. According to the court, the language of the Copyright Act and decisions interpreting it “provide no basis for a rule that allows the physical location or possession of an image to determine who may or may not have ‘displayed’ a work within the meaning of the Copyright Act.”

The court explained that the blogs and news outlets took active steps to display the photo by locating the Tweet on Twitter and then copying the Tweet’s URL and incorporating the URL and relevant code into the design of their webpage to embed it. The court further pointed out that a violation of the right of display can occur without a party making a copy of a photo.

While the court, in its decision, found that the embedding of the Tweet with the image was an infringement, the court also recognized that this was not the end of the story. The court did not rule on several defenses, such as whether Goldman had released the photo into the public domain by posting it onto Snapchat and whether the blogs and news outlets had engaged in a fair use of the photo for news reporting purposes. It will be some time before there is a decision on those defenses. Indeed, the court has permitted the parties to appeal the case for a decision on the question of whether there is infringement.

While waiting for more guidance from the courts, it is prudent to be careful about how you use Tweets and other online materials on your website. The court’s decision reinforces the point that just because something is available online it is not necessarily free for everyone to use.

McAllister Olivarius v. Mermel—Using a Domain Name for Leverage

Domain names have long been an area where people have felt that because a domain name is available for use they are free to use it as they see fit. Congress passed legislation in 1999 intended to curb such activity, and other steps were taken at the same time by other domain name stakeholders, but the fact remains that thousands of cases regarding the unauthorized registration of a domain name corresponding to someone’s trademark are brought each year.

A case involving Mark Myers Mermel, a former candidate for Lieutenant Governor of New York, demonstrates, once again, that domain names cannot be used for any purpose just because they are unregistered. In May 2012 Mermel retained the law firm of McAllister Olivarius to represent him in a dispute with Yale University. McAllister invoiced Mermel eight times between May 2012 and August 2014, but Mermel refused to pay the invoices. In 2016 McAllister filed a lawsuit against Mermel to recover the unpaid fees.

At some point, Mermel registered the domain name <mcallisterolivariustruth.com>. The website associated with the domain name bore the title “McAllister Olivarius TRUTH” on every page. The home page contained a reference to one of the McAllister attorneys representing Mermel. The attorneys page of the site listed two lawyers with no connection to McAllister and contained text about another law firm.

In July 2016 Mermel responded to one of McAllister’s written demands for payment by, as the court described, threatening to populate the website with select documents that, Mermel claimed, “would cast Plaintiff [McAllister] and its principals in a negative light with ‘other potential clients’ and ‘cripple if not close’ its business. Mermel then offered to forego this plan if ‘both parties would simply ‘walk away’ from the unpaid balance, or, alternatively, plaintiff [substantially] reduced its balance.” (internal citations omitted).

McAllister ultimately brought a claim for cybersquatting in December 2017, and Mermel, acting as his own attorney, moved to dismiss the case. The court refused to dismiss the case, explaining that the court had jurisdiction because the case presented a question under federal law and that McAllister had sufficiently alleged the elements of a claim for cybersquatting. In analyzing the cybersquatting claim, the court pointed out that Mermel had not used the website for criticism of McAllister, but rather to profit from his use of the domain name by leveraging it in order to obtain a significant reduction in his legal bill.

Practical Considerations

If you see something online that you would like to use for your own project, the safest course of action is to ask for permission to use it—and if you’re told that you can’t use, don’t go ahead and use it anyway. Asking shows respect for the creator, and that might get you further than you think. Or, seek out and use content that has been made available for free. Websites like Unsplash and Lif of Pix have stock photos that are free for use (just make sure that you read the license for the photo, and include any required attributions).

That said, even if something is an infringement, a creator might not want to act regarding that infringement. A movie studio, for example, may not act against websites that allow users to play trailers for new movies because they want word of the new movies to reach as broad an audience as possible. On the other hand, if a creator thinks that their work has been wrongfully used, they may take a very aggressive position and seek a significant monetary payment to settle a matter. And, perhaps most importantly, just because everyone else is doing it doesn’t mean that you can, or should.

Conclusion

In the movie Jurassic Park, one of the characters, on learning that the company behind Jurassic Park has been cloning dinosaurs, says “[y]our scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” The same applies in the internet context (although without the possibility of dinosaurs running amuck)—just because you can do something doesn’t mean that you should. With online content, thinking about whether you should do something can often save a lot of time and money in the future. And if you’re not sure, talk to your lawyer.