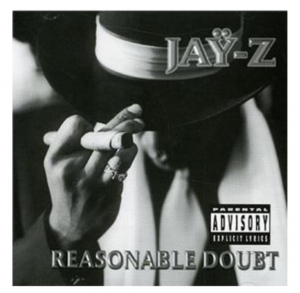

On June 15, 2021, Jay-Z, the iconic rap artist whose real name is Shawn Carter, filed a lawsuit in a federal court in California alleging that his rights of publicity and privacy were being violated by photographer Jonathan Mannion and Mr. Mannion’s company (“Mannion”). In 1996, Mannion had taken hundreds of photographs of Jay-Z, including the one featured on the cover of Jay-Z’s debut record album, Reasonable Doubt. See below:

That album launched Jay-Z’s career, and Jay-Z’s lawyers argue in the lawsuit that it launched Mannion’s career too. Mannion apparently has made a business of the images he shot of Jay-Z, featuring the images on his website, selling photographic prints for thousands of dollars as well T-shirts featuring the images. Oddly, Mannion even licensed the use of the images to others.

The Complaint asserts that:

- Through exceptional vision, persistence, and hard work, JAY-Z has attained an extraordinary level of popularity and fame in the United States and around the world. He is highly sought after to endorse commercial products and services using his name, likeness, identity, and persona.

- JAY-Z regularly receives substantial financial offers requesting permission for, and seeking the use of, his name, likeness, identity, and persona for licensing, endorsing, marketing, and promoting products, services, and performances.

- JAY-Z maintains strict control over whether and how his name, likeness, identity, and persona are used. JAY-Z restricts such uses and licensing to products, services, and performances that are of acceptably high quality and that otherwise tie to his personal and business objectives.

- JAY-Z never gave Mannion permission to resell any of the images. Nor did JAY-Z authorize Mannion to use his name, likeness, identity, or persona for any purpose. JAY-Z was careful to never give Mannion permission to exploit JAY-Z’s image in the photographs that Mannion took of JAY-Z.

An interesting window into the understanding at the inception of the relationship was alleged in paragraph 21 of the Complaint where Jay-Z states that he and his record company paid Mannion tens of thousands of dollars for the use of some of the photographs for Jay-Z’s album covers.

The Complaint is not kind in the picture it paints of Mannion, alleging:

- As JAY-Z achieved massive popularity, Mannion built his career on the basis of JAY-Z’s success.

- Over the years, Mannion has repeatedly exploited his relationship with JAY-Z to obtain photo-shoot assignments from many other rap and hip-hop artists. It is no secret that Mannion owes much of his career to JAY-Z.

- When JAY-Z and Mannion met in 1996, Mannion was a relatively unknown photographer, eager for any opportunity to advance his own ambitions.

- Mannion has built a career for himself based on his early association with JAY-Z. As a self-described “professional photographer,” however, Mannion knows or should know that he needs JAY-Z’s permission to sell photos containing JAY-Z’s image. Mannion does not care. It is an all-too-common occurrence in the music industry for a person in Mannion’s position to take advantage of up-and-coming stars who are not always in a position to vindicate their rights.

In the press, it is reported that Mannion’s lawyers, who claim that Mannion’s activities are protected by the First Amendment, asserted that “Mr. Mannion has created iconic images of Mr. Carter over the years, and is proud that these images have helped to define the artist that Jay-Z is today.” Mannion’s lawyer’s also reportedly said: “Mr. Mannion has the utmost respect for Mr. Carter and his body of work, and expects that Mr. Carter would similarly respect the rights of artists and creators who have helped him achieve the heights to which he has ascended.” It’s an interesting twist of perspective and an effort to sway equity and public opinion in Mannion’s favor.

The parties apparently had some dialog before the Complaint’s filing, as Mannion was asked to desist his activities but, while conceding that he needed a license to sublicense rights in the photographs, Mannion not only refused to desist, he “has in the last few weeks demanded that JAY-Z pay Mannion tens of millions of dollars to stop Mannion’s further exploitation of JAY-Z.”

The complaint’s allegations were made to support a claim for the violation of §3344 of the California Civil Code, which protects against the use of a person’s “name, voice, signature, photograph and likeness” for commercial purposes. Also asserted was a claim for the violation of Jay-Z’s right of publicity under California common law, which appears to provide broader rights than the code section itself. In any case, both violations can be asserted.

Most people do not realize that the right of publicity and the right of privacy are rights founded on state laws – either “state statutes/codes” which are passed by state legislators or on state “common law,” which is the law developed in Court decisions over time. California has both a state “code” as well as common law protections in place to vindicate a person’s right of publicity.

No federal laws are alleged to be violated, and interestingly, none are. In a dispute such as this, neither the Federal Copyright Act or the Federal Lanham Act (which protects trademarks and other designations of origin) are implicated. Mannion owns the copyright in the photographs, which rights are arguably abridged by the publicity right that Jay-Z has in his own image. Thus, Jay-Z can stop Mannion’s use of the photographs, but has to purchase a license from Mannion should he want to use his own photographs.

As most appreciate, a dispute such as this would never have arisen if Jay-Z had negotiated the right to own the copyright in the photos that were taken of him or had from the get-go restricted in writing the uses that Mannion could make. Similarly, the dispute would never have happened if Mannion had asked J-Zay to waive his right of publicity and privacy or if Mannion had gotten permission at the outset to use the images he was taking on his own account. Good legal counseling on either side could have avoided this dispute…but likely neither side could afford legal counsel at the time, or more likely they didn’t even appreciate the need. While it is understandable that these considerations were not addressed in 1996, one wonders why something was not worked out since then. Hindsight is a powerful teacher. What happened now to cause the suit is unexplained in the Complaint, as Mannion has been trading on the images for a long time. Because of that, it likely that Mannion will assert equitable defenses such as laches, estoppel and acquiescence although the extent to which these defenses would be appropriate is not clear.

If the matter is not resolved amicably, a Federal Court will need to balance publicity rights, on the one hand, and copyright rights and the First Amendment, on the other. This case and how it’s addressed will impact many artists and photographers. While the parties will likely resolve this case before the breadth of the First Amendment defense is tested, this is an opportunity to review the “right of publicity” in our own jurisdiction: New York.

New York’s right of publicity is contained in Sections 50 and 51 of Article 5 of the N.Y. Civil Rights Law. Section 50 provides for criminal charges to be asserted, but Section 51 allows a civil claim for the violation of a person’s name, portrait, picture, and voice. With respect to pictures, the statute has been broadly interpreted to include any recognizable likeness, not just an actual photograph and even to cover a representation of a person if it conveys the essence and likeness of an individual, albeit not completely photo-realistically. It has been found to cover use of sculptures, mannequins, and other three-dimensional “likenesses.” For there to be a violation, the use of a person’s identity must have occurred within New York State, “for advertising or trade purposes;” and without written consent. Thus, the statute protects against use to solicit sales of products or services. Thus Mannion would have liability under New York law as well. The statute provides not just injunctive relief but also permits the recovery of compensatory damages and punitive/exemplary damages. There is a one-year statute of limitations for a claim under Section 51; therefore, any recovery would be limited to the period within the limitations period.

Section 51 contains a long list of carve-outs which, expectedly, include a carve-out for use that occurs when the person is the subject of news. This is classic First Amendment protection. Apropos here, it also contains a carve-out for professional photographers against suits by their subjects. Delving more into the “photographer’s exception,” the statute says “…nothing contained in this article shall be so construed as to prevent any person, firm or corporation, practicing the profession of photography, from exhibiting in or about his or its establishment specimens of the work of such establishment, unless the same is continued by such person, firm or corporation after written notice objecting thereto has been given by the person portrayed….” Thus, while Jay-Z would be entitled to an injunction under New York law, his damage recovery would be limited to a one-year period. Mannion’s uses not only crossed the line, but he refused to stop when asked to do so. More importantly, Mannion would not have a valid First Amendment defense.

Back to California, the statute of limitations there is two years. Like New York, the California code contains carve-outs — for uses related to news, public affairs, sports, and politics. Courts usually focus on these statutory “safe harbors” when confronting right-of-publicity claims. The facts, in this case, do not implicate these statutory safe harbors. It seems that Mannion will need to rely on equitable defenses to the extent they are applicable and on the First Amendment defense which his attorneys have already raised in the media. A Court would ultimately determine that the Constitution does not excuse the breadth of Mannion’s activities, but that is a long way off.

A copy of the complaint is available here.