When I tell people that I represent clients in the restaurant industry, they often give me puzzled looks and ask me why restaurants would need any kind of intellectual property protection. The truth is that restaurants face the same kinds of issues as any other business, and generally need the same types of protection. Consider this article an attempt to digest those issues and best practices.

Whose Name is That?

Name protection is probably the first thing that people think of when identifying intellectual property concerns faced by restaurants, and with good reason. The press has been full of stories about disputes over restaurant names. For example, the former The Four Seasons space in New York City’s Seagram Building, is to be named “Landmark”, short for “Landmark Rooms”–though not even having opened, it was already the subject of a trademark infringement lawsuit brought by Landmarc restaurant, which has an outpost a mile away (the case has since been settled). In a case in Chicago, Wolfgang Puck is involved in a trademark dispute over the name “The Kitchen”. Katz’s Delicatessen, a client of ours, was involved in a dispute a few years ago with a food truck selling deli products that called itself “Katz and Dogz” and, referencing a well-known scene from the movie When Harry Met Sally, offered a “Reuben Orgasm” sandwich.

Unsurprisingly, the matter was resolved in favor of Katz’s Delicatessen.

It is not just restaurant names that should be protected. The names of menu items, particularly well-known or important ones, may also qualify for and require trademark protection. IHOP has a federal trademark registration for ROOTY TOOTY FRESH ‘N FRUITY, Denny’s has a registration for MOONS OVER MY HAMMY, and McDonald’s unsurprisingly has trademark registrations for BIG MAC. Where protection is asserted disputes are sure to follow, and menu item names are no exception; by way of example Carl’s Jr. was recently involved in a lawsuit in Utah regarding its Western Bacon Cheeseburger name. In another instance, we had to file a lawsuit on behalf of our client Burger Keeper, LLC, to protect its rights in FIVE NAPKIN BURGER, the name of its restaurant and a menu item; another restaurant had adopted the name “Six Napkin Burger” for one if its menu items. After the lawsuit was filed, the other side agreed to the entry of a consent judgment barring its use of “Six Napkin Burger.”

Proactive steps can help restaurants avoid these issues, however. Before adopting a name and slapping it on signage, menus, and other collateral, conducting a comprehensive trademark search for a restaurant or menu item name, together with legal advice about whether a proposed mark is protectable, can head off at least some such battles. For a search to be of any value, though, it must be conducted before the restaurant opens—a time at which restaurateurs are more focused on building out their space and promoting their new establishment to potential patrons. While there is often an understandable financial crunch at that time, you should balance the cost of paying an attorney to confirm that you may use your proposed name against the risk and cost that in using a name without clearing its status, you may find yourself the target of an enforcement action launched by a prior user of the same or similar name, and ultimately having to change your name, signage and menus after having incurred the time and financial cost of building the commercial identity of the restaurant around a potentially infringing trademark.

Furthermore, having a federal trademark registration can be a powerful asset in acting against infringers and copycats, and it is best to obtain a registration as early as possible. Most important of all, though, is to act as soon as possible against infringers. The longer you delay, the harder it will be to stop a third party’s bad behavior. Moreover, the more parties that use the same or confusingly similar name, the weaker your rights become, degrading the ability to protect and assert your rights.

That Looks Familiar….

Most restaurants will have a website where they post their menus and photos of their interiors and their meals. Sometimes these images will wind up on someone else’s website, as there is a common misconception that materials posted to the internet are available for everyone to use. This is not the case, and copyright registrations should be promptly filed for websites. A registration will be strong support for cease and desist letter to a third party who has taken images from your establishment’s site.

Images aren’t the only thing that can be copied–sometimes the unique design of a restaurant is e fodder for imitation. In a watershed ruling, however, the Supreme Court held that the look of a restaurant is protectable as trade dress. As is typical, though, trade dress can be difficult to establish and is disfavored by the courts. Still, restaurants have brought actions to enforce alleged trade dress rights in their overall design: for instance, Pearl Oyster Bar sued Ed’s Lobster Bar on this basis in 2007 (the case also involved allegations of theft of recipes); the case was ultimately settled. By the same token, in some situations, aspects of a restaurant’s look can be protected by a design patent, which protects novel ornamental designs.

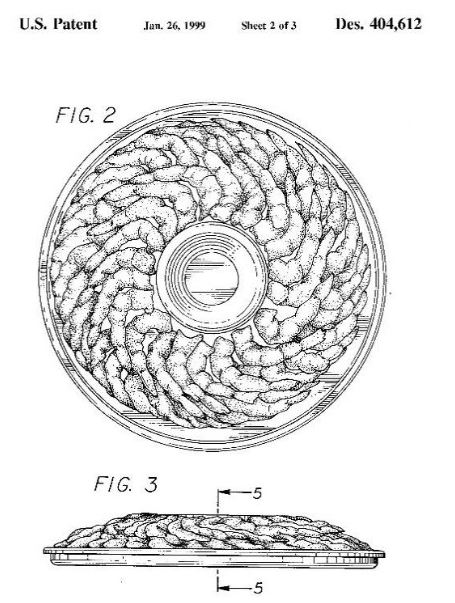

Can the plating of a specific dish be protected? While there are not many cases on this point, it appears that the answer is likely yes, by way of a design patent. In a 2002 dispute, Contessa Food Products owned a design patent for a “Serving Tray with Shrimp,” which depicted a round serving tray with a circular receptacle in the center for sauce. The shrimp are arranged in two layers, with the heads of the shrimp on the lower layer pointing towards the center and the tails pointing towards the edge of the tray. The shrimp in the upper layer are arranged in the opposite fashion, with tails overlapping heads in the lower tier.

Contessa successfully asserted its patent rights in a lawsuit against Conagra, as the Court concluded that Conagra’s dish misappropriated the unique design of Contessa’s plate.

Moreover, design patents can cover not only dishes, but the design of food items themselves, such as a unique shape for a pretzel. In some situations, the presentation of food can be registered as a trademark, but only upon a showing that consumers have come to associate the presentation with a particular source—think Pepperidge Farm’s Goldfish crackers, or a Hershey’s Kiss.

Is That my Recipe?

At a recent fundraising event for a culinary high school that I attended, one of the first questions I was asked was how a restaurant could protect its recipes from being taken by current employees if and when they departed for other jobs. My immediate response was that the best way to do this would be to keep the recipes secret (like the formula for Coca-Cola or KFC’s secret blend of 11 herbs and spices–although there were reports in 2016 that this had been disclosed). Employees should also be required to sign non-disclosure agreements preventing them from disclosing recipes. This can require a not inconsiderable amount of paperwork, but it is the primary way in which to protect recipes; the Copyright Office has long held that recipes are not protected by copyrights. Establishments employing this method of protection should make sure that their employees re-sign non-disclosure agreements once a year, to remind them of their obligations.

If someone devises a new and unique way of preparing a dish, or, for instance, using molecular gastronomy to combine foods to achieve a new flavor or taste, it might be possible to protect that invention by a utility patent. Utility patents generally cover new and useful products (including mechanical devices and chemical compositions) and processes (such as for making drugs and methods of genetic engineering, and some computer programs). Utility patents can be expensive and take several years to obtain, but they confer extremely valuable IP rights. As such, they have been sought by renowned chefs, including, Homaro Cantu of Moto restaurant in Chicago, who famously developed edible paper that tastes like cotton candy and which bears the following notice:

Confidential property of and © H. Cantu. Patent Pending. No further use of disclosure is permitted without prior approval of H. Cantu.

Conclusion

The sheer number of intellectual property lawsuits concerning the food service industry underscores not only the concerns faced by, but the opportunities available to restaurants. Obscure as they may be to the public at large, such IP issues are no doubt occupying the minds of restaurateurs, investors, and chefs. Seeking legal advice early in the process of developing a new restaurant concept or a new dish could be a recipe for maintaining the value of those assets.