Everyone has heard of Pfizer’s Viagra. Most people know that it is a “little blue pill”, even if they have not used it themselves. Some might even know that the pill is shaped like a diamond. This public awareness is a result of the outsized publicity and media attention that Viagra has received since even before its introduction. While that atypical media attention has a fairly obvious marketing benefit, it had another benefit that is less heard of but just as important.

Although generic drug inserts (such as those listing contraindications) MUST replicate those of corresponding brand drugs, like store brands in supermarkets, generic drugs often try to imitate the look of the brand-name counterparts as well. Unsurprisingly, this attempt at imitation can often result in litigation. Understanding what can and cannot be legally protected can help avoid litigation in the first place; if litigation nevertheless arises, understanding the contours of available legal protection can aid in developing an effective litigation strategy.

Loving the Way You Look

Probably the most common means of protecting a pill’s look is what is known as trade dress. The overall appearance of a pill includes features such as size, shape, color and color combinations. In determining whether a particular trade dress is protectable, the two most significant factors are functionality and distinctiveness.

Trade dress does not protect functional elements. A product feature is considered functional when the product would not work properly without that element or if that element affects the cost or quality of the product. The Supreme Court has said that disclosure of a particular feature in a utility patent is a good indication that something is functional. Another good indication that a feature is functional is when the feature is touted in advertising as making a product work better than competing products. Other factors courts consider in evaluating the functionality of trade dress are whether alternative designs are available and whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

If the look of a pill is not functional, then, according to the Supreme Court, the pill’s look is eligible for trade dress protection only if the party seeking protection can prove that the public has come to associate the look of its pill as indicating that the pill came from a particular source. This usually requires several years of active sales, advertising, and promotion. Sometimes, however, the media hype around a product can make the look of the product protectable as trade dress in a very short time span–think of the iPhone, for example. If the look of a pill does not function as an indicia of source, it cannot be protected as trade dress. And, as discussed further below, trade dress can be registered with the U.S. Trademark Office.

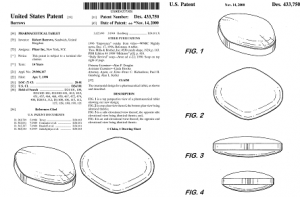

Another means of protecting the look of a pill is by design patent. While the pharmaceutical industry is very familiar with patents, design patents are often overlooked when considering available forms of protection. As shown by the legal battle being waged by Apple and Samsung, design patents can be very powerful. Design patents protect the ornamental design of a product or component of product. To qualify for design patent protection, the design must be 1) new; 2) “nonobvious” compared to prior designs in the marketplace or in prior patents; and 3) ornamental and not functional. In the U.S., a design patent application must be filed within one year of the product’s first public availability. If a design patent is granted, an object with a design that is substantially similar to the design claimed in the design patent cannot be made, used, copied or imported into the jurisdiction where the design patent is held for fifteen years.

The View From the Courts

A number of cases address whether the look of a pill can be protected by trade dress. An early case involved pills in the shape of hearts. In that case, Smith, Kline & French Labs had developed and marketed a heart-shaped pill with a score in the middle. The pill came in two different colors based on the ingredients. Smith, Kline & French Labs sued Heart Pharmaceutical Corp. for making a generic version the featured the same heart shape, the same score down the middle and the same coloring. The court found that the score was functional, since it enabled patients to break the pill in half to take a lower dose. Nevertheless, the court issued an injunction preventing the sale of the generic, since the court found that the heart-shape and the color were distinctive and only served to identify the manufacturer to the public.

A more recent case from 2003 had a different result. In that case, the court of appeals ruled that the size and color of Shire U.S., Inc.’s Adderall was not protectable as trade dress since those features were keyed to dosage amounts. Shire brought suit against Barr Labs, Inc. for producing a generic form of Adderall that looked similar to Shire’s Adderall pills, and the lower court ruled that there were differences between Barr’s generic form and Shire’s pills (Barr’s pills were a different shape and bore different markings), and that any similarities in color and size were functional and thus not protectable. The court of appeals agreed, explaining that the color and size of Adderall are directly related to the drug’s efficacy since there was evidence that maintaining a constant color and size between Adderall and Barr’s generic would prevent confusion among patients, and promote patient safety, acceptance and comfort.

So What Does It All Mean?

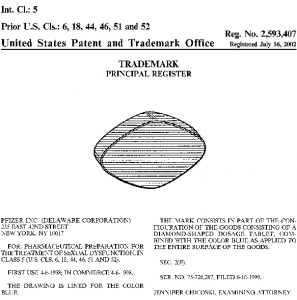

Viagra did not face these issues. The massive publicity surrounding the launch of that product made it much easier for Pfizer to claim, after a short period of time, that the look of Viagra was protectable. Indeed, Pfizer was able to secure a trademark registration from the U.S. Trademark Office for the look of its Viagra pills (shown below).

Additionally, Pfizer secured a design patent for the look of the Viagra pill, adding a second layer of protection. The entire design patent appears below.

In view of the trademark registration and the design patent, generic drug makers will not be able to use the look of Viagra for their generic products unless they obtain a license from Pfizer. But this is hardly the usual case. In most cases there is no bright-line test for determining whether the look of a particular pill is protectable or whether it may be freely used by others, as demonstrated by the cases discussed above.

Staying Protected From Improper Copying and From Litigation

For those cases that do not involve pills with the world renown of Viagra, a proactive approach to protection is required.

Developing a pill look that is protectable requires considerable planning from the start. Those working on the creation and “look” of a new pill should work together with their lawyers so that they can be certain that the pill’s look is not the result of functional elements, ensuring the maximum scope of protection. Similarly, the marketing team must work closely with the legal team to devise a promotional campaign that will cause consumers to associate the look of the pill with a particular source—the “little blue pill”.

Companies launching generic versions of drugs should likewise consult with their counsel to determine what elements of the brand-name product’s look can be used and which elements they should avoid using. In some cases this can require a study of design patents and trademarks obtained by the brand manufacturer as well as any applicable deign patents and trademarks held by generic manufacturers.

That close cooperation between the legal department and other corporate departments, while sometimes difficult to achieve, is well worth the effort, since it can be the key to avoiding protracted disputes.

Originally published on “Pharma Compliance Monitor“