Originally appeared on Law360, July 8, 2016.

The internet of things (“IoT”), broadly speaking, is a collection of objects with embedded sensors and electronics. Using sensors, internet-enabled objects such as refrigerators, automotive transmissions, and clothing, collect data and automatically communicate with other internet-enabled devices for processing. Collected data can be analyzed to made decisions, such as controlling connected devices, or to adjust what is being collected. Unsurprisingly, IoT patents generally fall into three areas: (1) features related to end devices to collect data or respond to controls; (2) network protocols and systems for communication; and (3) applications that make use of the collected data. In general, other pre-IoT industries have applied for and been granted patents in these same areas.

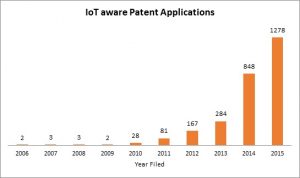

Companies are positioning themselves to get ahead of the patent game before the IoT technology tips from a being somewhat novel to being ubiquitous, having learned from the internet bubble and its floods of patents and later lawsuits, the smartphone wars and the like. The IoT and IoT patents are growing exponentially. For example, using the number of published U.S. patent applications with the phrase “internet of things” in the specification as a metric, from 2006-2015, there were 2,700 such “IoT aware” applications with fully 80 percent of these applications being filed in 2014 and 2015.

Among issued U.S. patents, only about 350 include the term “internet of things,” about 75 percent of which issued in just the past year. More broadly, a 2014 U.K. Patent Office study concluded that from 2004-2013 nearly 22,000 published patent applications worldwide directed to IoT technologies and smart internet-connected devices.1

Opportunities for patenting IoT-based inventions exist throughout the IoT design chain: the end devices, the sensors they use, the way devices connect to and communicate with other devices, the way data are kept secure or power is managed, system architectures, ways to exploit capabilities of an IoT environment, and so on. As with other patents, focus can be on new technologies, improvements to existing ones, or on specific components or broader systems.

One IoT-specific area relates to applications making use of an IoT infrastructure. Such applications likely will ultimately drive the market for IoT devices. However, this area of development — data collection, data analysis, and then doing something based on the analysis — lies squarely in the path of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2014 Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank decision addressing patent-eligible subject matter.2

In Alice, the Supreme Court held that abstract ideas alone are not patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101 unless the claim also contains “significantly more.”3 The Alice court did not define the contours of an abstract idea or what constituted significantly more but specifically stated that implementing an abstract idea on a generic computer system alone was not enough. 4 Since the Alice decision, many software and business method patents have been invalidated as not falling with the scope of § 101. Lower courts decisions and corresponding patent office guidelines following Alice make clear that inventions directed to collecting and analyzing data and using the result are at risk of being ineligible for patent protection.

In one recent IoT example, Jawbone accused Fitbit Inc. (and others) of infringing patents directed to wearable sleep and health monitoring systems.5 The asserted patents had claims directed to a system with several sensors, a processor, and a transceiver, and some claims further had a central monitoring unit.6 Referencing earlier decisions finding claims to data collection and analysis as unpatentably abstract, the court held that the claims were directed to an abstract concept — using sensors to collecting information to monitor health and wellness data. 7 The court further explained that the patentees “do not claim to have invented the compact sensors, processors, and transceivers that permit systems to be housed in a wearable device” and that there was nothing “substantially more” provided by the use of the “generic off-the-shelf components” recited in the claims or in packaging the components into a wearable device.8

Until last month, the 2014 DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com LP was the only case which successfully passed an Alice challenge on appeal. In DDR Holdings, the Federal Circuit found patent eligible claims because “the claimed solution is necessarily rooted in computer technology to overcome a problem specifically arising in the realm of computer networks.” 9

Further concrete guidance is set forth in the new Federal Circuit decision Enfish LLC v. Microsoft Corp.10 The Enfish claims are directed to a “self-referential” logical model for a computer database, which is contrastable with existing “relational” models. In Enfish, the court held that claims directed to a database model (in effect, directed to software and to improvements in computer-related technology) are not inherently abstract. The court also provided more general guidance: when making an initial determination of whether an invention is abstract, the inquiry should be whether the claimed invention provides an improvement in computer capabilities or instead invoke computers “merely as a tool.”11 Applying this test, the court held that a specific way to organize data in a database is not an abstract concept because, per the patent, the method provided benefits of “increased flexibility, faster search times, and smaller memory requirements.” The implementation on a general purpose computer was not fatal because the claims were “directed to an improvement in the functioning of a computer.”12

In contrast, only a week later (and in a decision authored by the same judge who authored Enfish), the Federal Circuit held that a claim directed to digital images captured using a cell phone and stored based on a classification system was invalid under Alice.13 Acknowledging Enfish, the court concluded that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of classifying and storing digital images in an organized manner and that the focus of the invention was not directed to any improvement to computer components. The court also held that the claims did not recite “significantly more.”

Applying these lessons, when seeking a patent on IoT applications, it is very important to frame and describe how aspects of the invention serve to improve the operation of the system or any of its components. For example, does the invention increase speed, reliability, or security of one or more components? Does the invention allow use of less memory, fewer central processing unit cycles, or less power? Does it increase flexibility of the system, or make updates or repairs to the system easier? Describing these technical effects in the patent specification can provide a basis for patent eligibility.

The flip side to obtaining patent protection is managing IoT infringement concerns. At least because thousands of potentially applicable patents might apply to an IoT technology, a patent clearance analysis may be quite beneficial. Such an analysis is intended to identify relevant patents to avoid, but because of the expansiveness of the space and broadness of present IoT solutions, no search can possibly be all encompassing and uncover all relevant patents. Complicating this is the rapidly expanding volume of pending IoT related applications, many of which may not even have published. In addition, patent aggregators and enforcement entities appear to be collecting broad-based patents applicable to IoT technologies, presumably with intent to enforce when the market has developed sufficiently.

To offset this concern, at least in part, industry players are forming their own organizations to aggregate patent pools and provide one-stop-shopping for industry players to obtain licenses. Still other efforts are directed toward creation of Standards bodies, such as ones specific to certain industries, conceptually as a means to accelerate innovation and deployment. Participants in such groups are typically obligated to identify relevant patents and offer them for licensing under fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms. However, these efforts are still in the early stages.

Risk can be mitigated in other ways as well. Infringement insurance is available, both conventionally and through defensive patent aggregators, but this can be expensive and limited in scope. Risk can also be mitigated through indemnification or similar agreements from part and system suppliers, but these agreements are often limited to the supplied products and may be difficult for small companies to obtain.

In summary, the IoT brings a wealth of potential benefits to consumers and businesses, but brings issues associated with patents along as well. Industry players need to be cognizant of the benefits and pitfalls of a rapidly growing and diverse space so as to position themselves relative to the many other players.

NOTES

[1] Eight Great Technologies The Internet of Things-A patent overview, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/343879/informatics-internet.pdf, p. 4

[2] 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

[3] Id. at 2355.

[4] Id. at 2357.

[5] In re Certain Activity Tracking Devices, Systems, and Components Thereof, ITC Investigation No. 337-TA-963.

[6] See Patent No. 8,961,413 for a “Wireless communications device and personal monitor“ and No. 8,073,707 for “System for detecting, monitoring, and reporting an individual’s physiological or contextual status.”

[7] In re Certain Activity Tracking Devices, Systems, and Components Thereof, Inv. No. 337-TA-963, Order No. 54 (U.S.I.T.C., April 27, 2016), Slip opn at pp. 12-13 and 22.

[8] Id. at 20, 23.

[9] 773 F.3d 1245, 1257_ (Fed. Cir. 2014). In DDR, the patented invention was directed to a way for a user to navigate from a host website to obtain information from a third-party merchant without losing the host website’s “look and feel”.

[10] Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., No. 2015-1244, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 8699, (Fed. Cir. May 12, 2016).

[11] Id. at *11-12

[12] Id. at *17-18.

[13] TLI Communs. LLC v. AV Auto., L.L.C. (In re TLI Communs. LLC Patent Litig.), No. 2015-1372, 2016 U.S. App. LEXIS 8970 (Fed. Cir. May 17, 2016).