By Diana Muller

In a recent article that appeared on The Wall Street Journal entitled “The Elements of Sneakers” the author starts with an interesting question: “What’s the last pair of shoes you bought? Let me guess: sneakers.”

The article goes on to state that the sneaker business hit $44 billion in sales last year in the United States. Obviously, the makers of performance athletic sneakers compete with one another. For the last few years the high fashion brands have also penetrated the market with quite expensive and unusual sneakers, although more simple and retro shoes seem to be the current trend. The reality is that no matter how fancy the sneakers are, the key to success in the marketplace has always been the strength of the connection between the product and the consumer. Especially in the sneaker world, there is significant amount of attention dedicated as to how recognizable trademarks, logos and designs are to consumers. Quality and performance are important, but sneaker companies have become so obsessed with the design of elements and logos that they are constantly creating so as to improve the recognition factor among consumers. Such recognition and identification are based on various elements of the athletic footwear such as a distinctive sole, a logo placed on the side of the shoe, a wordmark, or other symbols.

The history of Adidas’s Three Stripes logo and its unstoppable policy of protection and enforcement continues to catch the attention of IP lawyers. This year Adidas filed an opposition against what appears to be a five-stripe design created by J.Crew and has also filed 16 other cases in the Trademark Office involving trademarks featuring stripes. In each of the cases, Adidas alleges that consumers will confuse the design at issue with Adidas’ Three Stripe design, for which it has multiple registrations for its covering apparel and footwear. Among the companies that were challenged by Adidas are: Ideavillage Products Corp; Golden Gaming, LLC; Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama; and Memphis Basketball, LLC (Memphis Grizzlies).

The Notice of Opposition filed by Adidas against J. Crew claims that J.Crew’s design:

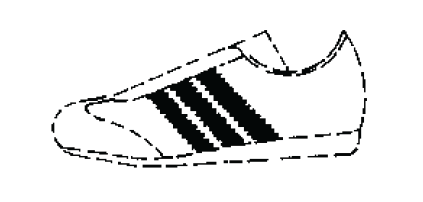

under application Serial No. 87/895,334 is confusingly similar to Adidas’s Three Stripe mark. The arguments by Adidas are based on its extensive use and trademark registrations for the Three Stripe design, which was originally adopted in 1952 and as early as 1967 in the United States. Representative samples of Adidas’ registrations are as follows:

(Reg. no. 1815956)

(Reg. no. 1815956)

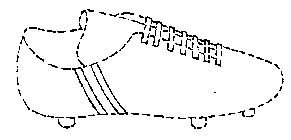

(Reg. no. 3708658)

(Reg. no. 3708658)

(Reg. no. 3029135)

(Reg. no. 3029135)

Moreover, the opposition lists Adidas’ longstanding relationships with famous universities and the many events, entities, and athletes that it has endorsed over the years, such as the soccer star Lionel Messi and the Boston Marathon. There is no question that the German company has significantly invested in marketing the Three Stripe mark and that it has been diligent in protecting it on a worldwide basis. However, consumer confusion is not necessarily apparent when the designs are not visually clear-cut copies of the Three Stripe mark. When dealing with logos or symbols, visual impression is quite important in determining the likelihood of confusion. J.Crew has taken the position that its design, which Adidas is objecting to, consists of five stripes in different colors. The opposition is pending (although temporarily suspended, presumably so the parties can discuss settlement).

In any event, Adidas has also sued many companies in Federal Court, such as Puma, Marc Jacobs, Sears, and Forever 21.

Adidas’ Three Stripe logo became famous due to the geniality of Adolf “Adi” Dassler who started making shoes in the early 1920’s with his older brother Rudolf. They both established a shoe company in Herzogenaurach, Germany. Their running shoes featured a “two stripes across the lateral and medial sides as a way of binding the shoe together and providing structure to the shoe”. The reality is that the design was a functional aspect of the shoe and not necessarily a protectible logo. Subsequent to World War II and due to the disruption in the business and certain issues between the two brothers, Rudolf started a new company that became “PUMA” and Adi started “Adidas”.

He developed his trademark “Adidas” but needed a logo to be used on the products as a source identifier. He then purchased the rights on the three stripes from the Finnish sportswear company Karhu for today’s equivalent of $1,800 and two bottles of whiskey. Adi added a Trefoild logo and his business became known as the Three Stripe company. There is no question that in the early 1970s the three bars or stripes became a distinctive logo. However, trademark logos of this nature such as the Chevron design developed by Pony International or the swoosh created by Nike were not that easily registered. The USPTO and many foreign trademark offices considered that these logos were ornamental designs and not necessarily distinctive trademarks.

Although there was a clear evolution regarding the allowance of design trademark registrations, in many instances, courts continue to be reluctant to grant rights to a combination of stripes or bars. For instance, Adidas lost a Three Stripe trademark battle in Europe. In a recent decision, a court in the EU ruled that the Three Stripe design has not acquired distinctiveness in the EU. This decision is the result of a dispute between the German company and a Belgian shoe manufacturer. Adidas claims that this decision has been limited to a particular design and will not have a great impact on its other portfolio of Three Stripe marks.

Given the presence of other competitors in the market, such as the French company Patrick, which has registered a two stripes mark:  under registration No. 1322256, the question is how strong Adidas’ position is in regard to a series of stripes presented in different colors and thickness.

under registration No. 1322256, the question is how strong Adidas’ position is in regard to a series of stripes presented in different colors and thickness.

Why it is so important in the current market to protect the logos that appear on the side of the athletic shoes as opposed to just the wordmark? The answer is evident: we live in a world of visual exposure where TV networks, media and social media are showing athletes and teams wearing clothing and athletic footwear depicting trademarks and logos. There is a subliminal marketing approach. The consuming public looks for the items that its favorite players are wearing, and they want to associate with these products. Logos and designs are many times more visible than words, especially during a televised game and/or a single athlete’s performance.

In addition to the enforcement actions against the sale of infringing designs and logos, athletic footwear companies have enforced their rights against competitors in regard to their advertising campaigns. For instance, Pony, Inc. instituted a lawsuit against Nike in 2009 regarding Nike’s use of the letter “V’” on its advertising campaign. Nike alleged this referred to “Victory,” but Pony considered it to be an infringement of its Chevron Design. The case was settled and ultimately dismissed when Nike advised Pony that its campaign would be discontinued after running its course.

The cost of trying to obtain protection and enforcing the companies’ rights in these logos is high but major companies make every effort to pursue actions against infringers and also pursue registrations for these designs on a worldwide basis. In addition, they enter in substantial endorsement and sponsorship agreements with sports figures and teams so that these parties will wear their products and depict their trademarks. Consequently, it is not surprising that Adidas would continue to sue companies for what it considers to be infringement of its Three Stripe mark or a similar logo. Indeed, there have been lawsuits brought by Adidas against other parties for the use of two or four stripes on clothing or related products.

In the U.S., there is an important precedent for Adidas. In 1994 Adidas filed an action alleging Payless Shoes willfully infringed Adidas’ trademark rights by selling athletic shoes with imitations of Adidas’ Three Stripe mark. The parties entered into a 1994 Settlement Agreement, and Adidas dismissed the suit. In November 2001, Adidas filed a new lawsuit claiming Payless violated the Settlement Agreement, alleging that Payless’ two and four stripe shoes infringed Adidas’ Three Stripe mark. The allegations included: federal trademark infringement; federal unfair competition; federal dilution; state trademark dilution and injury to business reputation; common law infringement and unfair competition; and unfair and deceptive trade practices. Payless asserted affirmative defenses of laches, waiver, estoppel, abandonment, acquiescence, unclean hands, trademark misuse, and contractual estoppel. Payless also counterclaimed for abandonment and cancellation of the Three Stripe mark, breach of contract, unfair competition and deceptive trade practices. Payless originally won on summary judgment; however, on appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed and send the case back for trial.

The lower court noted that although there may be minor differences between Payless’ stripe design and Adidas’ mark, what mattered was that the overall impression created by the marks was essentially the same, and it was very probable that the marks were confusingly similar to consumers. Additionally, the fact that Payless only used two stripes or four stripes did not matter because the court looked at the total effect of the infringing design and its likelihood of causing confusion in the minds of an ordinary purchaser. Ultimately, after a three-week trial, a jury found that Payless acted willfully and maliciously, or in wanton and reckless disregard of Adidas’ trademark and trade dress rights. The jury determined Adidas was entitled to actual damages, which totaled $30.6 million in royalties, $137 million of Payless’ profits, and $137 million in punitive damages.

A second appeal ensued after the trial, this time focusing on damages. Payless argued that the jury’s $305 million damages award was flawed, claiming that the royalty calculation was contrary to law, speculative, and arbitrary. Payless also argued that the award of profits plus a reasonable royalty constitutes impermissible double recovery, and that the awarding of profits goes against the Lanham Act’s prohibition against damages as a penalty. Finally, Payless argued that the punitive damages award in inequitable, violated the Due Process Clause, and federalism. The appellate court affirmed the jury’s figure of $30 million in reasonable royalties, reduced the profits award to $19 million because Adidas overstated profits and did not follow accounting principles, and reduced the punitive damages award to $15 million as a result of due process concerns and conditioned its decision on Adidas accepting the remittitur of the new punitive damages amount.

Whether Adidas’ Three Stripe mark is entitled to a broad scope of protection remains a question many IP practitioners are interested in. Ultimately, it is up to the trademark offices and the courts to decide whether a third party’s use of other stripe designs, such as the one in the J. Crew opposition, would infringe or dilute Adidas’s Three Stripe mark.