Design patents are used to protect the ornamental appearance of an innovation, such as an innovative shoe. Historically, in order to file for a design patent for a three dimensional object, figures ordinarily must be included showing the object from at least six different orientations (top, bottom, left, right, front, and back) and, if needed, at least one perspective view. The purpose has been to encapsulate the design in a sufficient number of views to leave no doubt as to the scope of the invention.

In addition, design application figures typically include both “solid” and “dotted” lines, where the solid lines indicate the claimed design and the dotted lines show portions of the object not claimed. For example, a particular shape of a shoe may be shown in solid lines but a particular buckle or certain aspects, which is part of the design, may not be claimed, so as to allow for different buckles or different striping (as an example) being used by others that could still result in an infringing design.

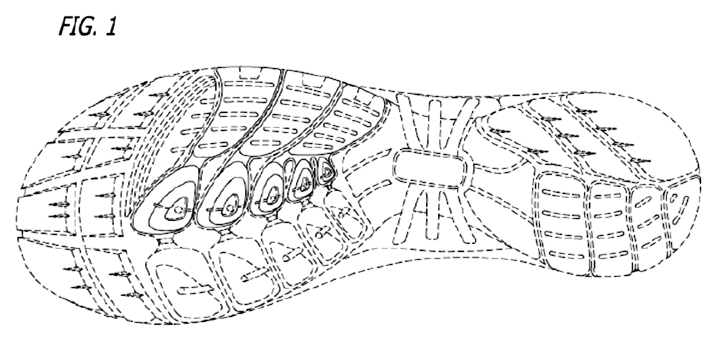

In a recent case at the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals (“CAFC”), In re Maatita, 2018 WL 3965892, a patent applicant successfully challenged the rule of showing the object in a series of figures as described above. In this case, the patent application was for a three dimensional Shoe Bottom. See FIG. 1, reproduced below.

In the case, the applicant merely provided two figures for the three dimensional shoe bottom. That is, despite the object being a three dimensional object, only two dimensions were shown.

Applying the “ordinary observer” standard, now the standard for determining infringement of a design patent, the CAFC held that “whether a drawing adequately discloses the design of an article, we believe that the level of detail required should be a function of whether the claimed design for the article is capable of being defined by a two-dimensional, plan- or planar- view illustration.” So, although an object might be three dimensional, it can still be capable of having its ornamental design disclosed in two dimensions.

As a result, when preparing figures for a design patent, an applicant should now consider whether fewer drawings provide sufficient clarity. There might no longer be a need for so many drawings.