On February 9, Hollywood’s biggest stars walked the red carpet outside of the Dolby Theater at Hollywood and Highland, and Parasite took home the Oscar for Best Picture. And while the fun in the night is in stargazing, looking at who is wearing what, and seeing what shocks and surprises the Academy has in store, behind the scenes there are enough intellectual property issues to keep more than one lawyer busy full time!

The Red Carpet

The red carpet at the Oscars is arguably the most famous red carpet in the world. But the red carpet is not a traditional red. Instead, it is an exclusive color that is more like a burgundy and is called Academy Red. To prevent others from copying the Academy’s red carpet, the precise specification of Academy Red, which is intended to flatter those walking and being photographed on it, is kept secret. Maybe the Academy should register Academy Red as a trademark—think UPS brown, Tiffany blue or Barbie pink, all of which are registered trademarks.

The carpet itself, however, is not the focus of attention on Oscar night. That would be the actors, directors, and other filmmakers who walk the red carpet, and, more particularly, their fashions. Those fashions (particularly the dresses) are almost immediately copied and sold. For example, a copy of the dress that Scarlett Johansson wore to the 2015 Oscars was available for purchase two days later. While protection for the cut of a dress is not available under U.S. law, design patents, copyrights and even trademarks/trade dress can be used to protect aspects of the look of a dress.

Oscar

For those in the movie industry, the point of attending the Academy Awards is to see who takes Oscar home (unless you’re one of the lucky nominees, in which case the point is to see if you get to take Oscar home!). So in a sense, the golden statuette of the bald man everyone wants to go home with is the center of attention on Oscar night.

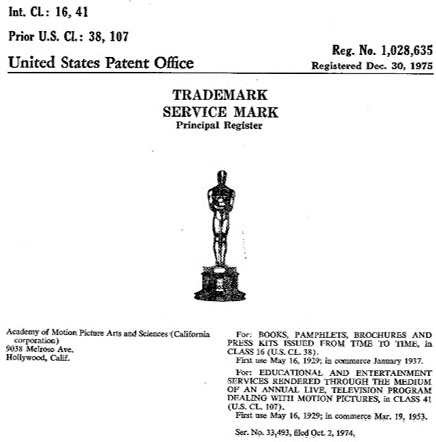

The Oscar statuette has been the center of attention in other ways. The configuration of the Oscar statuette is a registered trademark, and has been since 1975:

The Academy has been vigilant in protecting the Oscar statuette. It has taken action against sporting goods manufacturer Prince, Royal Caribbean and the ad agency Saatchi & Saatchi, all for making unauthorized use of the Oscar statuette in print or television advertising promoting their products. And in 2014, the Academy filed a lawsuit against a Texas man who was manufacturing, importing and selling fake Oscar statuettes on eBay and Etsy. The court ultimately ordered the man to pay the Academy $375,000 in damages for copyright and trademark infringement and enjoined him from manufacturing and selling Oscar statuettes.

It is not just counterfeit Oscar statuettes that the Academy pursues. Academy rules require that if an award-winner wants to sell their award, they must first offer to sell it to the Academy for $1. Award-winners who try to sell their award without first offering it to the Academy will hear from the Academy’s lawyers (whether the agreement can be enforced in court is a separate issue). While the policy is intended to prevent the statuettes from becoming a saleable commodity and to prevent knock-offs, that has not stopped their sale. By 2006 about 150 Oscars had been sold. The rule was not put into place until 1951, so Oscars that were awarded before then can be found in the marketplace.

Not only does the Academy have a trademark registration for the Oscar statuette, it of course has a registration for its OSCAR trademark. And as with the Oscar statuette, the Academy has been protective of its OSCAR trademark. Thus, it has pressured CNN to use the ® registration symbol in broadcasts after the OSCAR mark, even though the AP style manual counsels against using the registration symbol. Additionally, in 2010 the Academy filed a lawsuit against domain name registrar GoDaddy, accusing GoDaddy of cybersquatting for automatically placing parking websites with ads at domain names registered by third parties and which incorporated Academy trademarks. The Academy’s lawsuit was not successful because GoDaddy did not control the ads appearing on the websites and because of the automated way in which the parking sites were posted at the domain names; the court also held that GoDaddy acted in good faith because it had an objectively reasonable basis for believing that its conduct was lawful.

More recently, in 2016, the Academy sued Distinctive Assets, the creators of lavish gift bags given to all Academy Award nominees, for using the OSCAR trademark in an effort to appear as if the company and its gift bags were associated with the Academy. According to the lawsuit filed by the Academy, Distinctive Assets sent out press releases to major media outlets that caused the publication of stories, some critical of the gift bag phenomenon, which implied that the Academy plays a role in delivering the gift bags. The lawsuit was eventually settled with an agreement by which Distinctive Assets was permitted to continue distributing its gift bags so long as it does not use the Academy’s trademarks.

Does the Best Picture Mean a Lawsuit is Coming?

The Academy is not the only one in Hollywood that has its attorneys busy around Oscar time. Almost since the Academy Awards first started, the winner of the Best Picture award has frequently found itself embroiled in litigation. A sampling of these cases appears below.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

David O. Selznick, producer of the film, was never able to convince author Margaret Mitchell to authorize a sequel to this hit. After Mitchell died, MGM claimed that an agreement with her estate gave it the right to produce a sequel. Litigation ensued, and the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that MGM had not been granted any such right.

Casablanca (1943)

Warner Brothers turned a play called Everybody Comes to Rick’s by Murray Burnett and Joan Allison into this classic film. In 1983 Warner Brothers produced a prequel, which aired on TV. The playwrights sought a declaratory judgment that their original transfer of rights to Warner Brothers did not include the right to produce derivatives, such as a prequel, but the case was ultimately dismissed, with the New York Court of Appeals ultimately ruling that the playwrights had not retained any rights.

The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974)

In 2012, Paramount sued Mario Puzo’s estate over a sequel. The suit was filed after the estate announced that it was going to release a sequel novel called The Family Corleone. Paramount claimed that the contract it signed with Puzo in 1969 to purchase the rights to The Godfather precluded his estate from producing sequels. The estate counterclaimed against Paramount. The lawsuit was eventually settled, and the book went on sale.

Rocky (1976)

A screenwriter who was a fan of the Rocky franchise wrote a treatment for a film that involved a German boxer and a boxing match near the Berlin Wall. After the release of Rocky IV, the screenwriter sued for infringement; the court dismissed the copyright infringement claims on the ground that the treatment was not entitled to protection because it featured Sylvester Stallone’s characters without authorization.

Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

The author of Horowitz and Mrs. Washington, a book depicting the relationship between an old Jewish man and his African American physical therapist, sued the makers of Driving Miss Daisy, saying that they had copied his book. The court found otherwise, ruling that the only similarity between the works was the theme of a relationship between an elderly Jewish person and an African American employee.

Forrest Gump (1994)

Unlike many other cases, this case involved a claim of patent infringement. Forrest Gump featured special effects which were able to digitally alter old footage so that historical figures seemed to be speaking lines written by the screenwriter. The inventor of a similar process, used for altering lips in order to sub movies into different languages, sued for patent infringement, but ultimately was unsuccessful. The court ruled in favor of Paramount, in part because the inventor’s patent claims were directed to the translation of lip movements in foreign language films, and not the alteration of lip movements in the same language.

Titanic (1997)

A movie this big lived up to its namesake by giving rise to numerous lawsuits. One suit claimed that the Celine Dion song My Heart Will Go On was copied from a work by another musician; the court ruled otherwise. Another lawsuit involved the necklace that is central to the movie’s story; Twentieth Century Fox sued to stop a company from selling inexpensive replicas of the necklace. And at least two lawsuits were filed by pro se litigants claiming that the story had been copied from their works. Both cases were dismissed.

12 Years a Slave (2013)

A composer filed a lawsuit for copyright infringement, claiming that the music in the movie was substantially similar to his work. The case was ultimately withdrawn.

So at the end of the night, when Parasite was announced as the winner of the Best Picture award, we hope that while heading up to the stage to accept the award, someone called their attorney and warned them to be ready for a lawsuit!