On May 18, 2023, the Supreme Court released its opinion in the much-anticipated suit by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (“AWF”), against photographer Lynn Goldsmith (“Goldsmith”). The fact pattern in the case was quite simple – Andy Warhol used Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince to create a silkscreen image. Goldsmith argued this was copyright infringement. AWF argued that it was permitted fair use. The Supreme Court majority rejected the fair use argument and affirmed the Second Circuit, who had reversed the District Court to find infringement. While many sided with AWF, the Supreme Court found here that equity clearly aligned with Goldsmith.

In this fascinating case, the Supreme Court was only tasked to explain how they view the first of the four factors that assist courts in determining if an otherwise infringing use of an author’s copyrighted work is nevertheless a “fair use.” The common law “fair use” defense to infringement was codified in 17 U.S.C. § 107. That statute provides in relevant part that: “[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” To determine whether a particular use is “fair,” the statute sets out four factors to be considered: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The Supreme Court was only required to address the first factor of that test.

The Court viewed the first prong in the context of the purposes of the doctrine articulated in the language of the statute itself (rather than in legislative history). The purpose was so as not to stifle “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research.” On that basis alone, the Court could have determined that the doctrine was wholly inapplicable. Nevertheless, they went further and considered the “purpose and character of the use” which is simply reflecting again on the purposes set forth in the statute itself, as well as considering the appropriateness of allowing a use to be made because it is “fair” (meaning so as not to stifle the goals of allowing “fair uses”), despite the existence of copyright in the original work.

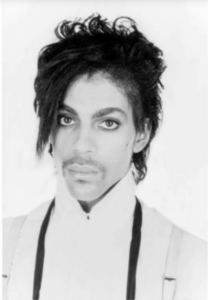

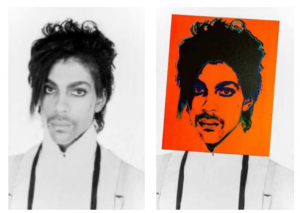

The simple facts and a picture of each work at issue will be instructive. Goldsmith took the following portrait photograph of Prince early in his career and indisputably owned rights in the photograph:

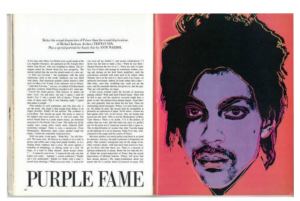

In about 1984, Vanity Fair obtained a one-time limited license from Goldsmith to use Goldsmith’s image as an “artist reference for an illustration.” With that license in hand, Vanity Fair hired Andy Warhol to create an illustration of Prince for its cover based on Goldsmith’s “reference.” Warhol thus used Goldsmith’s photo to create a purple silkscreen[1] portrait of Prince, which appeared with an article about Prince in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. The article and purple image is shown below:

The magazine credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400, pursuant to their agreement with her. No information was provided for what Warhol was paid.

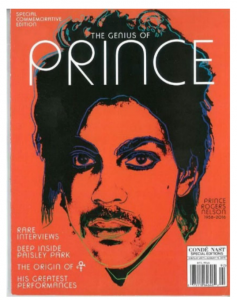

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company Conde Nast asked AWF (who had since obtained the rights to Warhol’s works as a result of Warhol’s own death) about reusing the 1984 purple image of Prince. Before Warhol’s own death, Warhol had actually created a series of “Prince Images” including what is called the “Orange Prince” at issue in this suit. Rather than license the so called “Purple Prince,” Conde Nast licensed the Orange Prince from AWF and paid AWF a $10,000 licensing fee. Neither AWF nor Conde Nast sought the permission of Goldsmith, nor did they credit Goldsmith. Goldsmith learned of Orange Prince when she saw it on the cover of Conde Nast’s magazine and presumably learned then as well of the entire Prince Series of Works that Warhol created and based on her “reference.” The Orange Prince magazine cover is shown below:

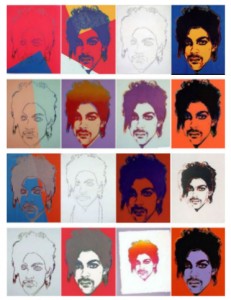

The Prince Series of works that Warhol created for his own purposes and without the approval of Goldsmith are shown below. None except Orange Prince were at issue in this suit. They include 14 silkscreens and 2 pencil drawings:

On seeing Orange Prince, Goldsmith notified AWF of her belief that her work was infringed. In response, AWF filed a declaratory judgment action seeking a declaration of non-infringement. Goldsmith countered with an infringement counterclaim.

Effectively conceding infringement (access and substantial similarity are a given), AWF argued that its use was a “fair use” because the Prince Series of works were “transformative.” This was another way of saying that the first fair use factor weighed in their favor. AWF claimed that they were within the fair use boundaries because the Warhol image “conveys a different meaning or message than the photograph.” A classic side by side display of Goldsmith’s portrait photograph and Warhol’s orange silkscreen portrait of Prince superimposed on Goldsmith’s portrait photograph (as carefully described by the Supreme Court) is shown below:

Given this, the Supreme Court, looking to the actual language of the first factor of the fair use privilege, explained that the “purpose and character” of the use did not favor AWF because the infringing use did not have a different meaning or message than the photograph, and the use did not have a “further purpose” or a “different character.”

The Supreme Court also acknowledged that “further purpose” or “different character” is in any case a matter of degree, and that the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations like the commercialism the Orange Prince. While it was clear that the fee that AWF earned when licensing the Orange Prince to Conde Nast substantiated the commercial purpose for which the work was used, the Supreme Court noted that commercialization alone was not dispositive as again it had to be weighed against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or a different character. A discussion of all three were important, but the Court simply could not find a further purpose or a different character in the Warhol Orange Prince than the purpose or character of the original photograph. The Court explained that “[b]oth are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince.” That Orange Prince was “instantly” recognizable as a Warhol did nothing to change that fact.

The Supreme Court used the opportunity of this case to explain its view of the meaning of the often battered word “transformative.” It noted that the term is not used in Section 107 itself. The Court explained that the term is used in the copyright statute only in the context of describing the exclusive bundle of copyright rights that belong to an author and specifically the right to create “derivative transformations” of the author’s work. The statute provides that the author has the exclusive right to prepare derivative works in “any other form in which the work may be recast, transformed or adapted.” (Emphasis added). The Court explained that an overbroad concept of a transformative use (as used by many in a Section 107 fair use analysis) would impinge an author’s exclusive right to create derivative works. Therefore, the Court noted that “[t]o preserve that [exclusive] right, the degree of transformation required to make ‘transformative’ use of an original must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.” (In contrast, the two dissenting justices argued that the majority’s view of “transformative” was too narrow and “hampers creative progress and undermines creative freedom”. The Supreme Court’s majority opinion critiqued the dissenting opinion throughout.)

In a footnote, the Supreme Court even distinguished between transformative use and transformative purpose and whether there had been a transformation of a work. If these distinctions are confusing, you are not alone. The analysis is subjective enough without reading in language into the statute that is not there and an important takeaway from the decision is that it just might be best of stay clear of using terms that go beyond the language of the fair use exception itself when attempting to come within its boundaries and simply be guided by the literal language in 107 when raising a fair use defense.

The opinion addresses important issues and it is a must-read for anyone who studies or creates art, never mind for anyone who dabbles in copyright law.

[1] The nature of a silkscreen work did not help AWF’s arguments, as Warhol’s practice was to apparently deliver a photograph to a professional silkscreen printer with instructions for alterations such as cropping and high contrasting to flatten the image. Once he approved it, the printer would reproduce the altered image like a photographic negative onto the screen, and then Warhol would place the screen face down on the canvas, pour ink onto the back of the mesh and pull the ink with a squeegee through the weave onto the canvas. This served as the “under drawing” over which colors would be hand-painted. This makes clear that Warhol’s works started with the photograph itself.